Following the Crossing Border Festival, I headed to the Vertalershuis Amsterdam (Translators‘ House Amsterdam) where I worked intensively for a week and a half with my mentor Jonathan Reeder on my English translation of an excerpt from Lize Spit’s Het Smelt, which recently won the NRC Book Competition’s prize for favorite book of the year.

For me, Het Smelt was a story that was all at once familiar and foreign. Mostly set in a small village in Belgium, it’s a coming-of-age narrative (my favorite kind) that jumps between a present-day nearly-30-year-old and her pre-pubescent self in the 1990s. Her tomboyish girlhood was marked by the usual small town escapades, cheap thrills, alcoholic adults, ennui – always with the same group of boys, her friends by default. But as an adult, she carries a dark memory, which isn’t revealed until three-quarters of the way through the book. But yeah, those boys who were supposed to be her friends? They weren’t. And then there’s this giant ice block that she starts schlepping around with her to take revenge. It doesn’t end well. Still, despite the macabre story, I laughed a lot while reading. Most of the time at things that really weren’t funny at all. That’s just good writing.

When I say the story was familiar, I’m talking about the growing-up in the 90s part. Lize Spit has a way with the little things: jawbreakers, making sculptures out of school lunches, hiding coins in socks, hit Spanish songs with hand motions, etc. Her heroine, Eva, is very much in her own head and her pre-teen reflections are taken very seriously. Spit writes with humor without self-deprecation. Her sentences have a way of turning themselves inside out, sometimes in illogical ways that can frustrate a translator. But I liked them anyway. Take the opening line of the book for example:

Original:

„De uitnodiging kwam drie weken geleden en was overdreven gefrankeerd. Het gewicht van de zegels die op hun buurt weer extra port moesten gekost hebben, stemde me in eerste instantie hoopvol: er zijn nog steeds dingen die elkaar mogelijk maken.“

The trouble here is that English lacks a single verb for stamping and mailing an envelope – postmarking? Nah. Then there was the question of how can stamps, or the adding of more stamps, actually make more stamps possible? Either way, you get what she means if you don’t think too hard. It’s the first sentence of the book, so it’s got to be just right. After much deliberation, here was the solution:

My translation:

„The invitation arrived three weeks ago in an overly stamped envelope. The weight of the stamps, which in turn must have required even more postage, at first gave me hope – there are still things that perpetuate their own existence.“

Jonathan and I labored over each and every sentence in my translation. Using every color highlighter in the pack, he color-coded all of my stumbling blocks. Words, phrases, expressions that weren’t quite right: sometimes I over anglified, other times I was still too Dutch. Jonathan’s translated A.F. van der Heijden, Peter Buwalda, not to mention the operas he surtitles for the Hollandsche Schouwberg – he knows what he’s doing. But still, he let me have my say. He pushed me to reflect and come up with my own alternatives. He struck through all of my extra littles, thats, alreadys, and alsos with the same editor’s eye that I myself have for texts written by the Dutch (who love the diminutive –je and extreme precision in the form of dat, al and ook ….among others, of course :)). I was surprised how quickly the calque creeps in.

When I say the text was foreign, I’m talking about the Belgian part, the Flemish part, the little-details-that-I-had-never-heard-of part. The story lives and breathes in these little details. For example, Eva uses a Curver to freeze her infamous ice block. What the hell is a Curver? Something akin to a Rubbermaid tub apparently. She listens to „The Ketchup Song“ on the radio. „What? You don’t know the Ketchup Song?!“ my Dutch colleagues in the house asked as they started doing some kind of turn-of-the-millenium Marcarena-esque dance in unison. Nope. Never made it across the Atlantic. Later, Eva goes into a shop and fills a paper candy bag with hosties and matten, which according to my research, are called satellite wafers and sour belts in English. When I was a kid we ate Warheads and Laffy Taffys. Then there is the meat counter where the butcher slices various kinds of worst. We Google-Image searched them all and discovered that they are all just – well – types of baloney.

As a translator, you constantly have to make decisions on what to do about these little things. Do you just translate them as they are and preserve the Belgian-ness of the book? Or do you convert them into something more familiar for your target readership? If you say „satellite wafer“, are you then obliged to explain that it is a sort of puffy sugary disk with candy beads rattling inside? Would Americans appreciate encountering a „Rubbermaid“ in a book they chose specifically for its foreign-ness?

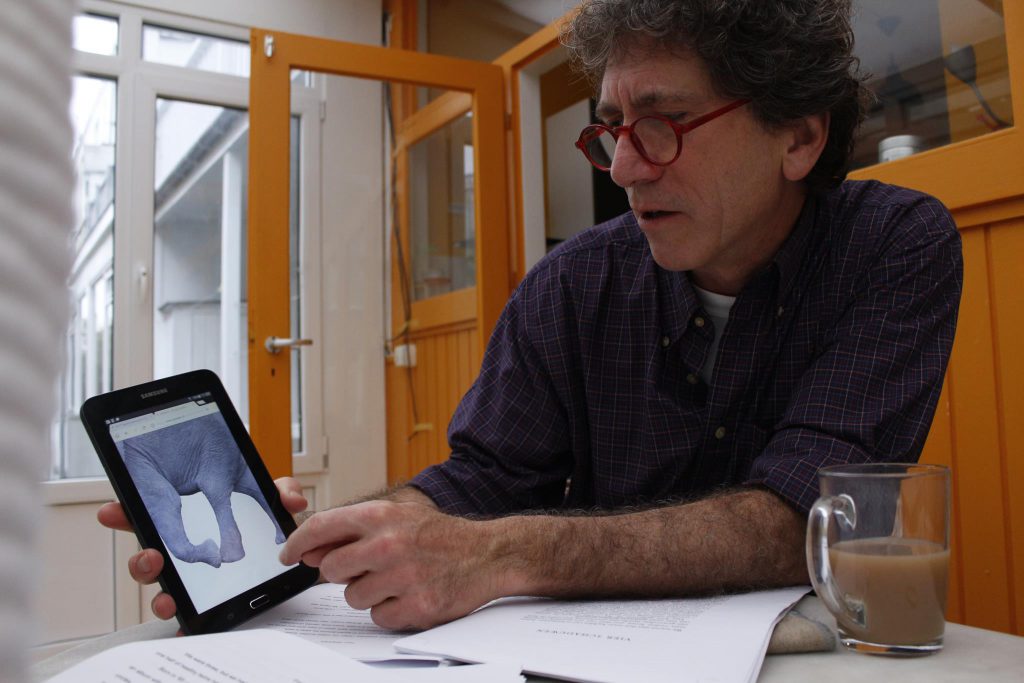

Speaking of Google-Image searching, we did a lot of that. In the photo above, Jonathan is looking up an image of „olifantenpoten“, which in the book was written under a picture of a little girl sitting on the potty. Seems strange, we thought. How could a child’s legs resemble elephant feet? But these are rabbit holes you should only go down so far. Lize Spit’s writing is full of these kinds of images: some make sense, some don’t, but either way, they sing. I discovered that the real goal – and the literary translator’s greatest challenge – is to write what the author would’ve written if she herself had had an English tongue. It’s true what they say: translators are writers. Literary translation is essentially re-writing the text. You have no choice but to make something new.

Here are a couple of my favorite bits from the translation process.

Original:

„De wanden zouden betegeld worden zodra daar geld voor was. Jolan ontdekte dat de holtes in de bakstenen prima houders waren voor tandenborstels. ‚Heel handing, in de tussentijd,‘ besloot mama. Jolan had het toen al berekend: er zit geen tijd tussen tijd.“

The challenge with this excerpt was the word play with „tussentijd“ or literally „between-time“, as if there could be time between time. But then you lose the expression in English. I think the choice of „meantime“ works well here.

My translation:

The plan was to tile it as soon as there was enough money. Jolan discovered that the holes in the bricks made perfect toothbrush holders. “So handy in the meantime,” Mama decided. But Jolan had already figured it out – there’s no time in meantime.

***

Original:

„De rolluiken van de winkel zijn bijna helemaal neergelaten, binnen schemert het. Er hangt muffe koelte tussen de volgestapelde rekken. Een te lang bewaard gebleven ochtend. Ik wacht en hou de deur van de woonruimte achter in de winkel in de gaten. Daar houdt Agnes zich schuil, vult ze fotokopieen van kruiswoordraadsels in. Wellicht staan er een zetel en een tafel, is er ook een keuken. Niemand kan dit bevestigen.“

My favorite part in this excerpt is „Een te lang bewaard gebleven ochtend“. Since fragments can come off choppy and awkward in English, I worked it into a dependent clause. I also love the little detail of „fotokopieen van kruiswoordraadsels“ rather than simply puzzles and the mystery of „Niemand kan dit bevestigen.“

My translation:

„The blinds in the shop are nearly completely rolled down, it’s dark inside. There is a musty coolness floating among the shelves, like a morning kept too long. I wait and keep a close eye on the private quarters at the back of the shop. That’s where Agnes holes up and does photocopies of crossword puzzles. Maybe there’s a table and chair in there, a kitchen too. No one can confirm this.“

***

Original:

„Jarenlang zouden we alles wat er in het dorp te vinden was uitspreken met dé of hét, alsof het onze bezitingen waren, tussen duim en wijsvinger vast te nemen. Alsof we na een lange oorlog met grote steden en omliggende dorpen de prototypes van een winkel en een slagerij te pakken hadden gekregen en deze vervolgens stevig hadden verankerd, in de buurt van de kerk en de parochiezaal, op loopstand van sowat alles, binnen handbereik van iedereen.“

In English, there is only one definite article: the. So the play on „dé of hét“ has to be altered to make sense later on in the paragraph. I also wanted to make sure that I got the imagery right here, as it so acutely describes Eva’s view of the village where she grew up.

My translation:

„For years we would refer to everything in the village with “the”, as if it all belonged to us, pinched between thumb and forefinger. As if, after a long war against big cities and surrounding villages, we had won the prototypes of a shop and a butcher and then anchored them down around the church and parish hall within walking distance of pretty much everything, within reach of everyone.“

I could go on with more examples, but I’ll stop here. I wouldn’t want to give away too much. In short, it was an enlightening process and a rare privilege to work with an experienced mentor. I’m extremely grateful to the Nederlands Letterenfonds (Dutch Foundation for Literature) for funding the program and the Vertalershuis for hosting.

Photos by Aura Xilonen, Mexican author of The Gringo Champion, who was staying at the house as well and working with her translator on a Dutch translation of her work. The book is coming out in English next year with the wonderful Europa Editions!

All excerpts are taken from Het Smelt by Lize Spit, Das Mag, 2016