“Language is my way of getting a grip on things, of maintaining control in certain situations. Your body is bombarded with zillions of sensory impressions, and by giving them a name, you make them one-dimensional again, manageable,” wrote best-selling Belgian author Lize Spit in her second blog post for The Chronicles. Actually, this is my translation of what she wrote. What she wrote was this:

“Taal is mijn manier om vat te krijgen op dingen, om controle te bewaren in bepaalde situaties. Een lichaam wordt gebombardeerd met tig zintuigelijke indrukken, door deze te benoemen maak je ze opnieuw eendimensionaal, beheersbaar.”

Sitting on stage between her and French translator Maud Gonne, I understood what she meant. All our ticks, fears, and nerves need words to latch onto. However fascinating foreign languages may be, however much we people with so-called “talenknobbels” like them, we still need the single dimension of our own language to really wrestle with ourselves.

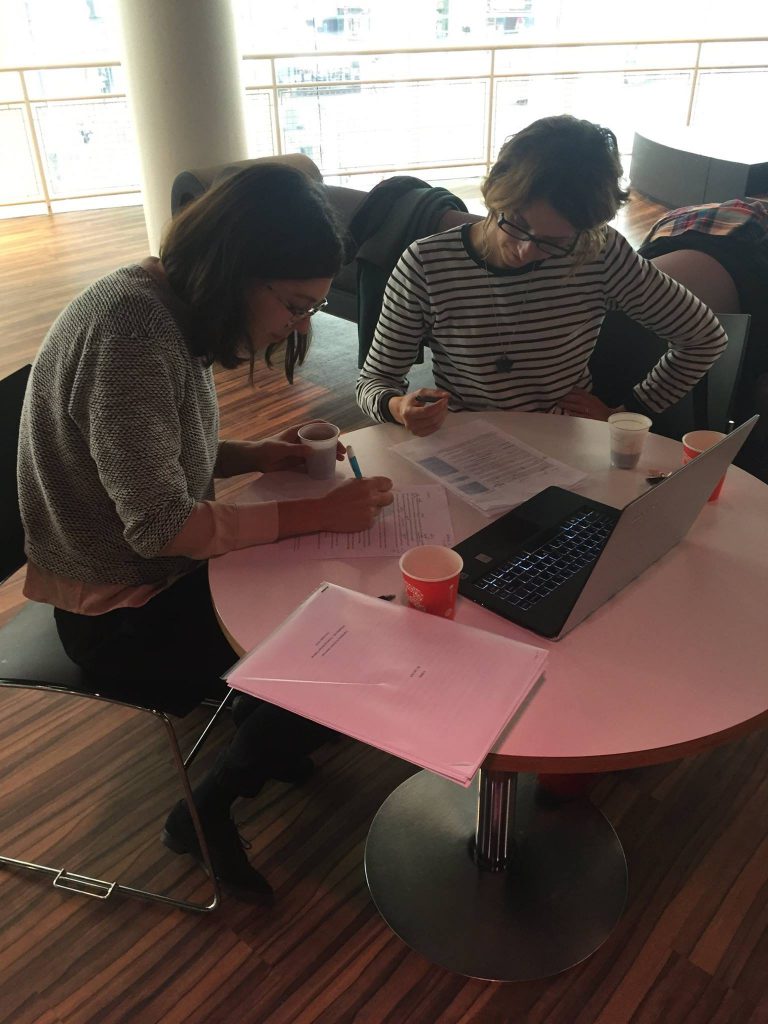

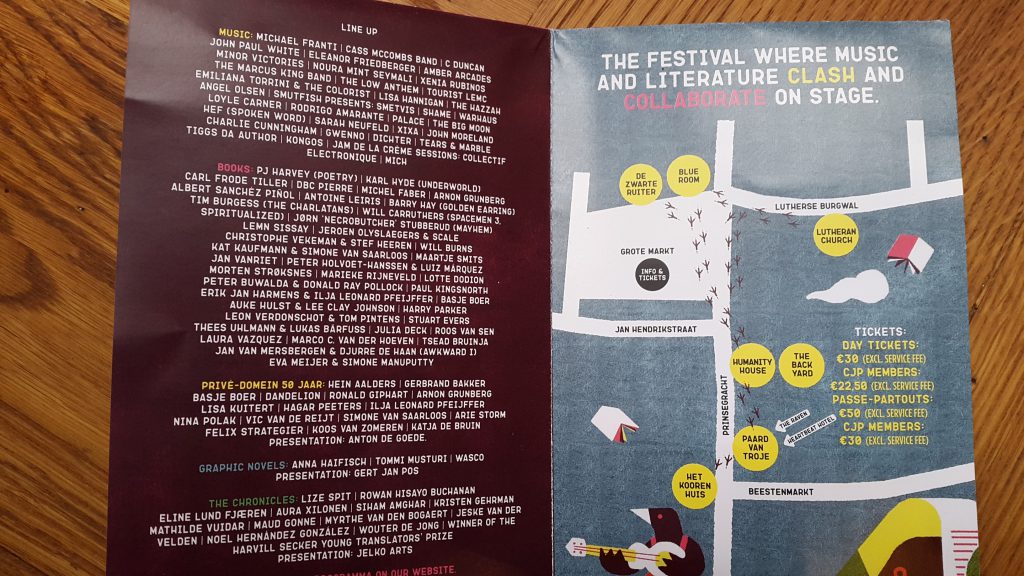

A branch of the Crossing Border Festival of literature and music, The Chronicles paired up young writers from around the world with emerging literary translators to create a multi-lingual narrative of the event. The writers submitted a series of five blogs: a prologue, three about the festival itself, and an epilogue. And we translators converted them into various languages, coached by more experienced mentors along the way. I worked with Michele Hutchinson, writer and English translator of well-known Dutch authors like Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer and Esther Gerritsen. Together we decoded unfamiliar Flemish words like lavabo (wastafel) and valling (verkoudheid) – Het Vlaams Woordenboek came in really handy here! We also worked through more complicated translator conundrums like how to untangle an untraceable Virginia Woolf quote, which had been taken from a Swedish book in Dutch translation, and translate it back to English (see Blog 1) or how to go about translating French and German words that appear in a Dutch text (see Blog 3). In some cases, I wanted days to mull over a single line, but we had just a few hours before our translations went live on the site.

Other than translating, the best part about the festival for me was spending time with the authors and other translators. Meeting young writers who have been so successful, talking about their process, all of the risks they take, discovering that they too have a “little dictator” marching around in their head (see Blog 4) – it made the whole literary world feel within reach. We translators also got to involve them in what we do, discussing the challenges we face in not just translating, but actually re-writing their texts.

When you’re starting out in literary translation, you worry constantly about fidelity to the original text, about preserving the author’s words at all costs. But then you meet the author who says, “No, just make me sound good in English,” and you’re liberated. You’re free to find creative solutions. You can look at a sentence and ask yourself, “Okay, if this author were writing in American English, how would she have said this?” You can look at yourself and say, “You’re a writer too you know.” And then, all of a sudden, you start becoming a much better translator.

On Saturday night of the festival, Lize Spit read from the first chapter Het Smelt and my English translation appeared on the screen behind her. The following week, during my residency at The Amsterdam Translator’s House, I had the opportunity to work on this translation intensively with another mentor – but that’s for another post. Stay tuned!